Released on June 10, 1994, "Speed" was the pinnacle of the very specific sort of action film that we saw in the late '80s and early '90s. Thanks to an amalgam of ingredients -- an inventive original score, a relative lack of computerized effects, a narrative that focused on human beings and an enigmatic, wild-eyed villain -- "Speed" played like a roller-coaster ride. As Roger Ebert called it at the time, the bomb-on-a-bus thriller was "an ingenious windup machine."

When we're talking about "Speed," 1988's "Die Hard" comes to mind, and rightfully so: "Speed" director Jan de Bont was the cinematographer on "Die Hard," and writer Graham Yost quickly found his script described by producers as "'Die Hard' on a bus." Later re-written for production by none other than Joss Whedon (who lost his credit to Writers Guild of America bylaws), the film was a box-office smash for Keanu Reeves and provided relative newcomer Sandra Bullock with her breakout role. As "Speed" turns 20 years old, HuffPost Entertainment spoke with some of the folks behind the film, to piece together what made it such a classic of its kind.

I. The Score

Let's begin with the score, which we kindly request that you listen to as you read:

There's something about Mark Mancina's score that really takes "Speed" to the next level. If you recall, it is very present in all of the major moments of the film; rather than quietly building suspense in the background, the title track plays prominently throughout. As Mancina recalled, he "wanted the theme to play the character of the bus, representing incredible danger, and also heroic power, because they are safe on that bus (until it blows up)." de Bont further mentioned that he wanted something with a more realistic energy than "the typical Hollywood movie score," one that could be modeled after "what you might hear from someone's headphones on a bus."

In setting out to score the film, Mancina stumbled upon the idea to incorporate sound sampling from the bus itself. Instead of using a timpani or other traditional drums, he played with the tone of a hammer hitting the bus or a giant tire being hit with a mallet. Now, you can buy such libraries in their entirety, but in 1994, this kind of edgy, metallic percussion -- which now characterizes most action film scores -- was a new idea. (Mancina knew someone working with this kind of sound library at the time, and the rest is audible history.)

Although scores like the one we hear in "Speed" have influenced action movies, that kind of acoustic presence has become much harder to find. "The music plays a very distant character in action movies and superhero movies nowadays," Mancina said. He's right: How many films can you think of that have a theme like "Speed"? Studios have become more cautious, steering away from their music having an identity, and that kind of risk-assessment almost robbed "Speed" of Mancina's work as well. By the time de Bont found Mancina through Hans Zimmer's studio, 20th Century Fox already had already hired Michael Kamen to score the film. ("They already knew they had a hit, so why not just be safe?" Mancina speculated about the studio's decision.) Fortunately de Bont wanted something more active with a contemporary element, so he specifically sought out Mancina for his rock and roll background (he produced for the band Yes) and youthful sensibilities.

II. A Sense Of Momentum (That Doesn't Rely On Special Effects)

Unlike, well, any action movie in recent memory, "Speed" was produced for the rather paltry sum of $30 million. (For absurd reference, Adam Sandler's "Jack and Jill" was allotted a reported budget of $79 million.) But that didn't stop the film from delivering all the thrills that are now created by a gratuitous amount of CGI. "My biggest aim was making it all look real," de Bont said.

![speed]()

There's a bus jump and a real mushroom cloud of an explosion at the airport, but relatively speaking these "bigger" scenes are limited in scope. Looking back at what he called "a simple but extreme" film, de Bont remembered there were a mere six scenes that incorporated effects. He noted that "these were more visual effects that were later composited, rather than the special effects we know today." The bus jump, for example, was done with a stunt driver, who actually made the jump with no missing roadway, completely destroying two vehicles in the process. "I wanted to make sure he felt the reality of the situation as well," he said.

De Bont noted that after "Speed" tested well with audiences, it was given a slight budget increase for things like the elevator scene at the beginning of the film. Although, most of the adrenaline rush is still supplied by an extremely kinetic approach to cinematography. Most scenes are shown through fast moving shots that play up what you might call the speed of "Speed." This kinetic approach was further facilitated by "a specific system of rigs" throughout the bus, including a platform under the bus, bungee cords and pulleys which allowed wide and rapid coverage of the tight-packed space. "I wanted it to always feel like the audience was always traveling with the passengers," he said. "There was nothing static about it -- the camera was almost as nervous as the people in the bus."

De Bont's style also boasts a certain cleanness, which he explains as much less "extensive" than bigger action movies. There are sparks, sure, but the tendency to cloak things in smoke or explosives is very limited (more on how that played into the humanity of the narrative in a bit).

"I had worked with directors on big movies," de Bont said, "and experienced very quickly what happens when the special effects become such a big part of the movie. Basically, each time you see a special effect, an audience is aware that something’s changed ... I always feel that the more you can touch it, the more you can relate to it, the better the reaction of the audience and the more they stay in the movie."

"When you get to the bus jump -- or any absurd moment in the film -- the question is: Is the audience going to go with you?"

The writing, too, lent the film its sense of momentum. A huge part of conceptualizing "Speed" -- which Yost did on spec -- was figuring out the "puzzle" of maintaining the pace of the film by adding obstacles on to the goal of survival. This aspect of the narrative, which the New York Times later referred to as "ingenious trickery," maintained a very careful balance, which relied on careful measure of the audience's willingness to go along for the ride.

"The thing is that, when you get to that moment, when you get to the bus jump -- or any absurd moment in the film -- the question is: Is the audience going to go with you and say, 'That was awesome. This is a great movie, and this is fun.' Or is the audience going to say, 'That’s ludicrous.' And get up and walk out?" Yost admits that no one knew what the audience reaction would be, but he does have an inkling as to what made it work. "Just the way Keanu and Sandy perform, the way Jan shot it, the dialogue Joss wrote and the structure that I came up with ... when the bus does the jump, the audience is on board, and they stay with us the rest of the movie."

As for the way they performed, Reeves remembered that jump and other fantastically ridiculous moments in the film, where he and Bullock worked together to play it straight. "There was this vulnerability and openness [with her]," Reeves said. "We would both look at each other every once in a while and go, 'This is crazy, but, let's play it for real.'" There was a similar connection not just with Bullock, but all of the characters trapped in the bus. "It was intense and fun," Reeves said, "But between all of the actors and actresses on the bus there was a sense of community."

![speed]()

Much of that structure allows "Speed" to maintain the rush that keeps the audience along for the ride. Yost spoke about his concept, which was inspired by an un-produced Akira Kurosawa script, and later Andrey Konchalovskiy’s "Runaway Train." Working over the idea with his father, Yost decided to dismantle the linearity of a train (which, in the film, is unable to stop because of the inaccessibility of its brakes). "I thought, 'A bomb would be better, that would be more dynamic, and scarier,'" he explained, "And then I thought, a train is just so linear, you know where a train is going. It’s just going to head out into the country and then you get everyone off, and everything’s fine ... going 50 mph in L.A. traffic is absurd, but it's certainly scarier."

III. The Psychologically-Driven Villain

For Dennis Hopper's character (Howard Payne), as de Bont said, "the monetary gain was almost secondary." He's driven by a vengeance against the bomb squad and a long-founded obsession with the weapon that makes him much more complex than the average action film villain. That makes the film more compelling than it might have been, had the antagonist's sole goal been procuring ransom, and all of that unscripted depth was the work of Hopper.

![dennis]()

As Yost remembered, "In 1994, Dennis Hopper was America's most beloved psychopath." Yet his role in "Speed" was a later development in the production process. Initially, Yost played around with the idea of having Jack's partner Harry (Jeff Daniels) play the villain. With the original script, he presented an idea in which it was later revealed that Harry had betrayed Jack and orchestrated the entire scheme. One of the producers later picked up on the intrigue of the villain being someone who was fascinated with bombs as a concept. "The idea of having him on the bomb squad lent him years of experience dismantling bombs, but also a certain obsession with their intense [danger]," Yost explained.

Yost said that Whedon gave Hopper more material than was in the original screenplay, and Whedon remembers planning for a different sort of character than Hopper brought to the screen. "I wrote a very straight forward, though a little off-center guy -- don't get me wrong, he's blowing people up, he's not okay -- who is weirdly thoughtful," Whedon said. "When Dennis Hopper comes in, he’s going to do what he does ... he’s going to Dennis Hopper it up. So, to me, it was strangely discordant. He’d walk in and change a sentence, and say, ‘I’m going to do this with it,’ and it plays, but if you actually look at what he’s saying, it’s not enormously grandiose.

De Bont further emphasized how Hopper brought the twisted man we saw to life. "He did all of those things himself," de Bont said. "It's hard for an actor, when the antagonist and the protagonist have only a few scenes together." Instead, Hopper developed the character by becoming hyper sensitive to Howard's motivations as they extended beyond the ransom. For example, when the first bus blows up in the beginning of the film, "you see his excitement over the fact that this thing that he made actually worked, and that deeply personal thing really set up the entire movie."

Despite the fact that they only had those few moments together, Reeves fondly remembers Hopper's work. "From a performance standpoint, he brought a humor and a reality to it," he says. "I mean, it was so heightened! With the revenge of this spurned guy, you know the bitterness, the regret. Yet, there was something sympathetic about the character as well, and Dennis just had such a warm heart and soul. I think he made that character, again, accessible and believable, yet fun."

IV. The Humanity Of The Narrative

At its core, "Speed" is an action film, but it also has elements of disaster and suspense movies, with a criminal twist.

"Instead of a building on fire or the after effects of an earthquake or whatever, the situation, the disaster that these people are going through is this manufactured one of a bomb on the bus," Yost said.

Another major part of de Bont's lack of reliance on special effects was the way "Speed" played on the very human reaction to that action-packed disaster of an experience. For de Bont, the most important part of pulling this film together was the reality of the way his characters interacted with the danger surrounding them.

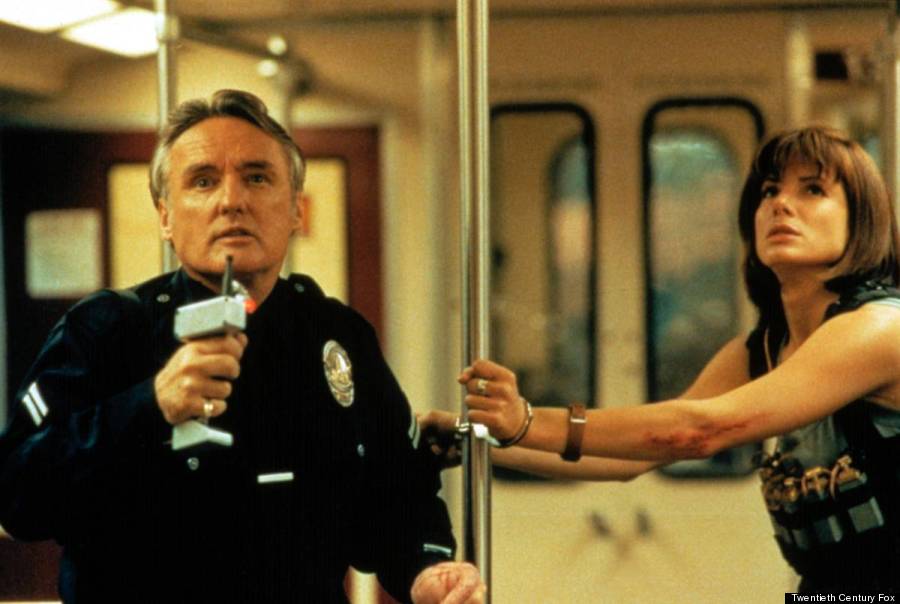

![speed]()

There's a certain empathy to "Speed" that is perhaps lacking in most other straight action films. The obvious comparison here is "Die Hard." Both scenarios are contained, which (as Yost puts it) helps viewers "get a greater sense of the peril these people are experiencing." Because of that, our empathy lies not just with the hero fighting some absurd obstacle. "Speed" gives us direct access to those lives in danger and whether they will survive. Although, as Yost noted, "in 'Speed' we actually spend much more time with the specific victims."

It was in working on "Die Hard" as the director of photography that de Bont first picked up on the importance of actors' reactions. He saw his role in holding the camera as the initial audience, and found the way the actors interacted with him after their scenes was enhanced when there was a closeness and sense of reality. "I feel like my whole idea for ['Speed'] was to be with the characters as much as possible, to let the actors do as much as the stunts themselves. Don’t rely on the stunt doubles and covers and stuff like that, but train them –- and, of course, let them do the effect in a non-dangerous way ... it is more realistic, but also, you can understand why the actor or the character reacts in a certain way ... unlike when they anticipate something on a green screen."

"We can all put ourselves as a passenger on that bus and imagine what we might be feeling."

"We can all put ourselves as a passenger on that bus and imagine what we might be feeling," Joe Morton (Capt. McMahon) said when remembering the film. "It’s a very human experience ... it’s not just the hero's story in 'Speed,' the action was the human action of getting to one place or another or achieving a goal."

That noted, there's something about Jack that follows in the footsteps of the thoughtful action hero pioneered by "Die Hard."

"'Speed' was part of moving out of a hyperbolic era, to the type of film that understands that everybody matters ... it's based on saving these people, it's not based on killing the bad guy," Reeves said. "But I look to the progression to films like the "Matrix," and I think there's the idea of the peaceful warrior germinating in ['Speed'], and I think that's important."

Whedon also spoke about meeting with Reeves to conceptualize the character. "The was a huge change from this rootin'-tootin' maverick to being a guy with a problem he must solve ... whose goal is to diffuse the situation." He noted that the particularly maverick-y line (and catch phrase of the film) "Pop quiz, hot shot" came from Reeves ad-libbing, and was most certainly not in the script.

In her breakout role as Annie Porter, Sandra Bullock personified the experience of the folks Jack was protecting, but the importance of everyone on the bus was not lost on de Bont, who specifically sought out actors with theater background to play his victims. You'll note that -- with the help of a stunt driver positioned in the back -- Bullock was actually driving the bus and not in a studio lot or with a green screen, but through the street.

Again, de Bont emphasizes the way the lack of reliance on special effects increases that humanity. He mentioned that, with some coaxing, Reeves performed much of his own stunt work -- perhaps most notably, rolling out from under the bus on a wired dolly (that "giant skateboard" type thing). At first, he did not want to step from the car to the bus, but de Bont talked him down. "He said 'It's way too dangerous,' and I told him it was basically like stepping onto an escalator. You just move up!" And once he got Reeves on board, the other actors followed suit.

Reeves is hesitant to say he did his own stunt work, but does vividly remember stepping from the car to the bus. "The shot in the film is a stunt man, but I got to do it once." He remembered Jan's urging for everything to be as real and visceral as possibly, and said he was always game for that, despite the fact that the only other traditional action film he'd done by 1994 was "Point Break."

"I tried to do as much as I could," Reeves said. "The stunt coordinator Gary Hymes really took care of me and came up with inventive ways of putting me in those situations. Through harnessing he got me under the bus at 30 mph."

Morton, too, actively participated in action sequences. He remembered actually flying in the helicopter scene, and compares that to his work on later action films.

"The guy who was flying our helicopter was one of the stunt drivers from the television series 'Whirly Birds.' So, that was very different from what they do today," he said. "I mean, I did a film called 'Paycheck' [with Ben Affleck] where I was, again, supposed to be in a helicopter, and they literally just raised the helicopter two feet off the ground for insurance purposes and didn’t really fly it, but in 'Speed,' we were flying around, actually following the buses."

When we're talking about "Speed," 1988's "Die Hard" comes to mind, and rightfully so: "Speed" director Jan de Bont was the cinematographer on "Die Hard," and writer Graham Yost quickly found his script described by producers as "'Die Hard' on a bus." Later re-written for production by none other than Joss Whedon (who lost his credit to Writers Guild of America bylaws), the film was a box-office smash for Keanu Reeves and provided relative newcomer Sandra Bullock with her breakout role. As "Speed" turns 20 years old, HuffPost Entertainment spoke with some of the folks behind the film, to piece together what made it such a classic of its kind.

I. The Score

Let's begin with the score, which we kindly request that you listen to as you read:

There's something about Mark Mancina's score that really takes "Speed" to the next level. If you recall, it is very present in all of the major moments of the film; rather than quietly building suspense in the background, the title track plays prominently throughout. As Mancina recalled, he "wanted the theme to play the character of the bus, representing incredible danger, and also heroic power, because they are safe on that bus (until it blows up)." de Bont further mentioned that he wanted something with a more realistic energy than "the typical Hollywood movie score," one that could be modeled after "what you might hear from someone's headphones on a bus."

In setting out to score the film, Mancina stumbled upon the idea to incorporate sound sampling from the bus itself. Instead of using a timpani or other traditional drums, he played with the tone of a hammer hitting the bus or a giant tire being hit with a mallet. Now, you can buy such libraries in their entirety, but in 1994, this kind of edgy, metallic percussion -- which now characterizes most action film scores -- was a new idea. (Mancina knew someone working with this kind of sound library at the time, and the rest is audible history.)

Although scores like the one we hear in "Speed" have influenced action movies, that kind of acoustic presence has become much harder to find. "The music plays a very distant character in action movies and superhero movies nowadays," Mancina said. He's right: How many films can you think of that have a theme like "Speed"? Studios have become more cautious, steering away from their music having an identity, and that kind of risk-assessment almost robbed "Speed" of Mancina's work as well. By the time de Bont found Mancina through Hans Zimmer's studio, 20th Century Fox already had already hired Michael Kamen to score the film. ("They already knew they had a hit, so why not just be safe?" Mancina speculated about the studio's decision.) Fortunately de Bont wanted something more active with a contemporary element, so he specifically sought out Mancina for his rock and roll background (he produced for the band Yes) and youthful sensibilities.

II. A Sense Of Momentum (That Doesn't Rely On Special Effects)

Unlike, well, any action movie in recent memory, "Speed" was produced for the rather paltry sum of $30 million. (For absurd reference, Adam Sandler's "Jack and Jill" was allotted a reported budget of $79 million.) But that didn't stop the film from delivering all the thrills that are now created by a gratuitous amount of CGI. "My biggest aim was making it all look real," de Bont said.

There's a bus jump and a real mushroom cloud of an explosion at the airport, but relatively speaking these "bigger" scenes are limited in scope. Looking back at what he called "a simple but extreme" film, de Bont remembered there were a mere six scenes that incorporated effects. He noted that "these were more visual effects that were later composited, rather than the special effects we know today." The bus jump, for example, was done with a stunt driver, who actually made the jump with no missing roadway, completely destroying two vehicles in the process. "I wanted to make sure he felt the reality of the situation as well," he said.

De Bont noted that after "Speed" tested well with audiences, it was given a slight budget increase for things like the elevator scene at the beginning of the film. Although, most of the adrenaline rush is still supplied by an extremely kinetic approach to cinematography. Most scenes are shown through fast moving shots that play up what you might call the speed of "Speed." This kinetic approach was further facilitated by "a specific system of rigs" throughout the bus, including a platform under the bus, bungee cords and pulleys which allowed wide and rapid coverage of the tight-packed space. "I wanted it to always feel like the audience was always traveling with the passengers," he said. "There was nothing static about it -- the camera was almost as nervous as the people in the bus."

De Bont's style also boasts a certain cleanness, which he explains as much less "extensive" than bigger action movies. There are sparks, sure, but the tendency to cloak things in smoke or explosives is very limited (more on how that played into the humanity of the narrative in a bit).

"I had worked with directors on big movies," de Bont said, "and experienced very quickly what happens when the special effects become such a big part of the movie. Basically, each time you see a special effect, an audience is aware that something’s changed ... I always feel that the more you can touch it, the more you can relate to it, the better the reaction of the audience and the more they stay in the movie."

"When you get to the bus jump -- or any absurd moment in the film -- the question is: Is the audience going to go with you?"

The writing, too, lent the film its sense of momentum. A huge part of conceptualizing "Speed" -- which Yost did on spec -- was figuring out the "puzzle" of maintaining the pace of the film by adding obstacles on to the goal of survival. This aspect of the narrative, which the New York Times later referred to as "ingenious trickery," maintained a very careful balance, which relied on careful measure of the audience's willingness to go along for the ride.

"The thing is that, when you get to that moment, when you get to the bus jump -- or any absurd moment in the film -- the question is: Is the audience going to go with you and say, 'That was awesome. This is a great movie, and this is fun.' Or is the audience going to say, 'That’s ludicrous.' And get up and walk out?" Yost admits that no one knew what the audience reaction would be, but he does have an inkling as to what made it work. "Just the way Keanu and Sandy perform, the way Jan shot it, the dialogue Joss wrote and the structure that I came up with ... when the bus does the jump, the audience is on board, and they stay with us the rest of the movie."

As for the way they performed, Reeves remembered that jump and other fantastically ridiculous moments in the film, where he and Bullock worked together to play it straight. "There was this vulnerability and openness [with her]," Reeves said. "We would both look at each other every once in a while and go, 'This is crazy, but, let's play it for real.'" There was a similar connection not just with Bullock, but all of the characters trapped in the bus. "It was intense and fun," Reeves said, "But between all of the actors and actresses on the bus there was a sense of community."

Much of that structure allows "Speed" to maintain the rush that keeps the audience along for the ride. Yost spoke about his concept, which was inspired by an un-produced Akira Kurosawa script, and later Andrey Konchalovskiy’s "Runaway Train." Working over the idea with his father, Yost decided to dismantle the linearity of a train (which, in the film, is unable to stop because of the inaccessibility of its brakes). "I thought, 'A bomb would be better, that would be more dynamic, and scarier,'" he explained, "And then I thought, a train is just so linear, you know where a train is going. It’s just going to head out into the country and then you get everyone off, and everything’s fine ... going 50 mph in L.A. traffic is absurd, but it's certainly scarier."

III. The Psychologically-Driven Villain

For Dennis Hopper's character (Howard Payne), as de Bont said, "the monetary gain was almost secondary." He's driven by a vengeance against the bomb squad and a long-founded obsession with the weapon that makes him much more complex than the average action film villain. That makes the film more compelling than it might have been, had the antagonist's sole goal been procuring ransom, and all of that unscripted depth was the work of Hopper.

As Yost remembered, "In 1994, Dennis Hopper was America's most beloved psychopath." Yet his role in "Speed" was a later development in the production process. Initially, Yost played around with the idea of having Jack's partner Harry (Jeff Daniels) play the villain. With the original script, he presented an idea in which it was later revealed that Harry had betrayed Jack and orchestrated the entire scheme. One of the producers later picked up on the intrigue of the villain being someone who was fascinated with bombs as a concept. "The idea of having him on the bomb squad lent him years of experience dismantling bombs, but also a certain obsession with their intense [danger]," Yost explained.

Yost said that Whedon gave Hopper more material than was in the original screenplay, and Whedon remembers planning for a different sort of character than Hopper brought to the screen. "I wrote a very straight forward, though a little off-center guy -- don't get me wrong, he's blowing people up, he's not okay -- who is weirdly thoughtful," Whedon said. "When Dennis Hopper comes in, he’s going to do what he does ... he’s going to Dennis Hopper it up. So, to me, it was strangely discordant. He’d walk in and change a sentence, and say, ‘I’m going to do this with it,’ and it plays, but if you actually look at what he’s saying, it’s not enormously grandiose.

De Bont further emphasized how Hopper brought the twisted man we saw to life. "He did all of those things himself," de Bont said. "It's hard for an actor, when the antagonist and the protagonist have only a few scenes together." Instead, Hopper developed the character by becoming hyper sensitive to Howard's motivations as they extended beyond the ransom. For example, when the first bus blows up in the beginning of the film, "you see his excitement over the fact that this thing that he made actually worked, and that deeply personal thing really set up the entire movie."

Despite the fact that they only had those few moments together, Reeves fondly remembers Hopper's work. "From a performance standpoint, he brought a humor and a reality to it," he says. "I mean, it was so heightened! With the revenge of this spurned guy, you know the bitterness, the regret. Yet, there was something sympathetic about the character as well, and Dennis just had such a warm heart and soul. I think he made that character, again, accessible and believable, yet fun."

IV. The Humanity Of The Narrative

At its core, "Speed" is an action film, but it also has elements of disaster and suspense movies, with a criminal twist.

"Instead of a building on fire or the after effects of an earthquake or whatever, the situation, the disaster that these people are going through is this manufactured one of a bomb on the bus," Yost said.

Another major part of de Bont's lack of reliance on special effects was the way "Speed" played on the very human reaction to that action-packed disaster of an experience. For de Bont, the most important part of pulling this film together was the reality of the way his characters interacted with the danger surrounding them.

There's a certain empathy to "Speed" that is perhaps lacking in most other straight action films. The obvious comparison here is "Die Hard." Both scenarios are contained, which (as Yost puts it) helps viewers "get a greater sense of the peril these people are experiencing." Because of that, our empathy lies not just with the hero fighting some absurd obstacle. "Speed" gives us direct access to those lives in danger and whether they will survive. Although, as Yost noted, "in 'Speed' we actually spend much more time with the specific victims."

It was in working on "Die Hard" as the director of photography that de Bont first picked up on the importance of actors' reactions. He saw his role in holding the camera as the initial audience, and found the way the actors interacted with him after their scenes was enhanced when there was a closeness and sense of reality. "I feel like my whole idea for ['Speed'] was to be with the characters as much as possible, to let the actors do as much as the stunts themselves. Don’t rely on the stunt doubles and covers and stuff like that, but train them –- and, of course, let them do the effect in a non-dangerous way ... it is more realistic, but also, you can understand why the actor or the character reacts in a certain way ... unlike when they anticipate something on a green screen."

"We can all put ourselves as a passenger on that bus and imagine what we might be feeling."

"We can all put ourselves as a passenger on that bus and imagine what we might be feeling," Joe Morton (Capt. McMahon) said when remembering the film. "It’s a very human experience ... it’s not just the hero's story in 'Speed,' the action was the human action of getting to one place or another or achieving a goal."

That noted, there's something about Jack that follows in the footsteps of the thoughtful action hero pioneered by "Die Hard."

"'Speed' was part of moving out of a hyperbolic era, to the type of film that understands that everybody matters ... it's based on saving these people, it's not based on killing the bad guy," Reeves said. "But I look to the progression to films like the "Matrix," and I think there's the idea of the peaceful warrior germinating in ['Speed'], and I think that's important."

Whedon also spoke about meeting with Reeves to conceptualize the character. "The was a huge change from this rootin'-tootin' maverick to being a guy with a problem he must solve ... whose goal is to diffuse the situation." He noted that the particularly maverick-y line (and catch phrase of the film) "Pop quiz, hot shot" came from Reeves ad-libbing, and was most certainly not in the script.

In her breakout role as Annie Porter, Sandra Bullock personified the experience of the folks Jack was protecting, but the importance of everyone on the bus was not lost on de Bont, who specifically sought out actors with theater background to play his victims. You'll note that -- with the help of a stunt driver positioned in the back -- Bullock was actually driving the bus and not in a studio lot or with a green screen, but through the street.

Again, de Bont emphasizes the way the lack of reliance on special effects increases that humanity. He mentioned that, with some coaxing, Reeves performed much of his own stunt work -- perhaps most notably, rolling out from under the bus on a wired dolly (that "giant skateboard" type thing). At first, he did not want to step from the car to the bus, but de Bont talked him down. "He said 'It's way too dangerous,' and I told him it was basically like stepping onto an escalator. You just move up!" And once he got Reeves on board, the other actors followed suit.

Reeves is hesitant to say he did his own stunt work, but does vividly remember stepping from the car to the bus. "The shot in the film is a stunt man, but I got to do it once." He remembered Jan's urging for everything to be as real and visceral as possibly, and said he was always game for that, despite the fact that the only other traditional action film he'd done by 1994 was "Point Break."

"I tried to do as much as I could," Reeves said. "The stunt coordinator Gary Hymes really took care of me and came up with inventive ways of putting me in those situations. Through harnessing he got me under the bus at 30 mph."

Morton, too, actively participated in action sequences. He remembered actually flying in the helicopter scene, and compares that to his work on later action films.

"The guy who was flying our helicopter was one of the stunt drivers from the television series 'Whirly Birds.' So, that was very different from what they do today," he said. "I mean, I did a film called 'Paycheck' [with Ben Affleck] where I was, again, supposed to be in a helicopter, and they literally just raised the helicopter two feet off the ground for insurance purposes and didn’t really fly it, but in 'Speed,' we were flying around, actually following the buses."